In a quiet hospital room in Chongqing, China, a 68-year-old brain-dead man became part of a world-first medical experiment. Scientists implanted a kidney into his body—one that wasn’t a natural match for his blood type. Yet, for two days, it worked just fine. No immune suppression. No lucky match. Just cutting-edge biochemistry at play.

The organ, originally Type A, had been chemically transformed into Type O—a universal blood type. Using enzymes from the human gut, researchers were able to erase the antigens that usually cause organ rejection. For 48 hours, the converted kidney functioned normally inside the patient before the immune system caught up and rejection began.

This breakthrough, described in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is a first step toward creating universal donor organs that could be transplanted into nearly any patient—no matter their blood type.

Compatibility

If you’ve ever donated or received blood, you know how important blood types are. It’s the same with organs. A mismatch usually triggers hyperacute rejection, a violent immune response that can destroy a transplant in minutes.

Type O blood is considered the universal donor because it lacks the A and B antigens that the immune system flags as threats. The same logic applies to organs—Type O kidneys are in high demand because they can go into almost anyone.

But there aren’t enough Type O organs to go around. People with Type O blood wait longer and face more complications. That’s why scientists started thinking differently—not about suppressing the recipient’s immune system, but about changing the donor organ itself.

Enzymes

The real stars of this breakthrough are enzymes found in the human gut. These enzymes naturally strip away antigens on cell surfaces. Researchers at the University of British Columbia figured out how to use them to remove A antigens from the blood vessels in a donor kidney.

Think of it like wiping a red “A” off the organ’s ID card and replacing it with a blank slate. With no A markers, the immune system had nothing to attack—at least for a short while.

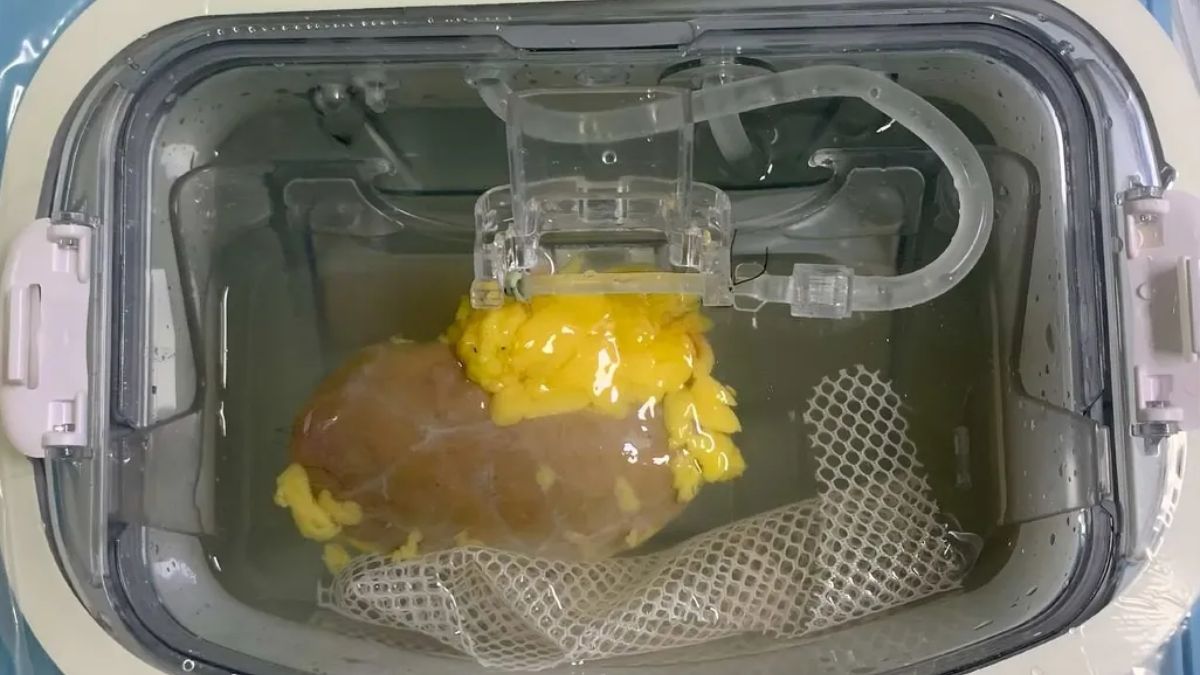

The team perfused the kidney with enzymes for two hours. After the process, the organ showed no trace of blood type identity and was ready for testing.

Transplant

The kidney was then transplanted into the body of a brain-dead patient, whose family had consented to the experiment. Importantly, no drugs were given to suppress the immune system. The goal was to see how the organ would perform on its own.

For the next 48 hours, the kidney worked: it produced urine, maintained blood flow, and showed no immediate signs of rejection. But by the third day, as the body’s natural processes began to restore the A antigens, the immune system reacted and rejection kicked in—right on schedule.

Still, that two-day window of success is a big deal. Until now, this kind of conversion had only been tested in lab settings, never inside a human body.

Urgency

This research comes at a critical time. In the U.S. alone, over 92,000 people are currently waiting for a kidney transplant. On average, 13 people die each day while waiting. For people with Type O blood, the wait can be even longer.

Converting more organs to Type O could drastically expand the donor pool, making life-saving transplants available to far more people, and faster.

Here’s why that matters:

| Blood Type | Can Receive From | Can Donate To |

|---|---|---|

| A | A, O | A, AB |

| B | B, O | B, AB |

| AB | A, B, AB, O | AB |

| O | O | All types |

As you can see, O is the most versatile donor type—but it’s also the hardest group to match as a recipient, which is why this kind of innovation could be game-changing.

Impact

This new method also sidesteps one of the biggest problems in organ transplantation: time. Living donors can undergo immune conditioning before the transplant. But deceased donor organs need to be used quickly—usually within hours. That leaves no time to prepare the recipient.

By modifying the organ, not the patient, doctors may be able to use more deceased donor kidneys across a wider range of recipients.

It could also reduce racial disparities in transplant access. A 2022 report found that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to have Type O blood but less likely to find a matching donor.

Challenges

Despite the success, there are still hurdles. The enzymes don’t create a permanent change. Eventually, the antigens return, and rejection resumes.

Future research may involve combining this method with traditional immunosuppressive therapy to extend the organ’s compatibility time. Clinical trials in living patients are likely on the horizon, but we’re still a few years away from routine use.

That said, this is one of the most important advances in transplant science in decades. If perfected, it could end blood-type matching as a major barrier in organ donation.

The long waitlists. The failed matches. The racial and blood-type inequities. This discovery won’t fix them all—but it’s a bold, smart start.

FAQs

What was converted in the experiment?

A Type A kidney was changed to Type O using enzymes.

How long did the converted kidney function?

It worked normally for about 48 hours before rejection began.

Did the patient receive immune-suppressing drugs?

No, no immune suppression was used in the experiment.

Can this be used for all organs?

The technique shows promise but has only been tested on kidneys so far.

Why is this important for transplant equity?

It could expand access for hard-to-match blood types like Type O.